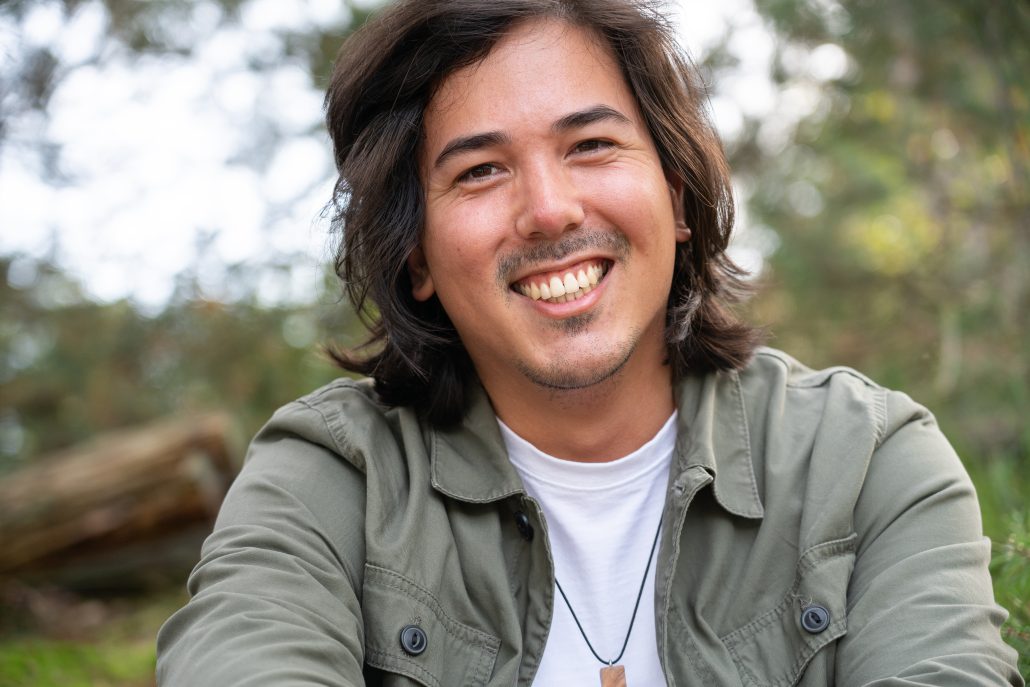

And now, artist JOEY VELBERG hopes to inspire others to face some of their demons, too.

Words by Tim van Erp, main picture Marjoke Smits

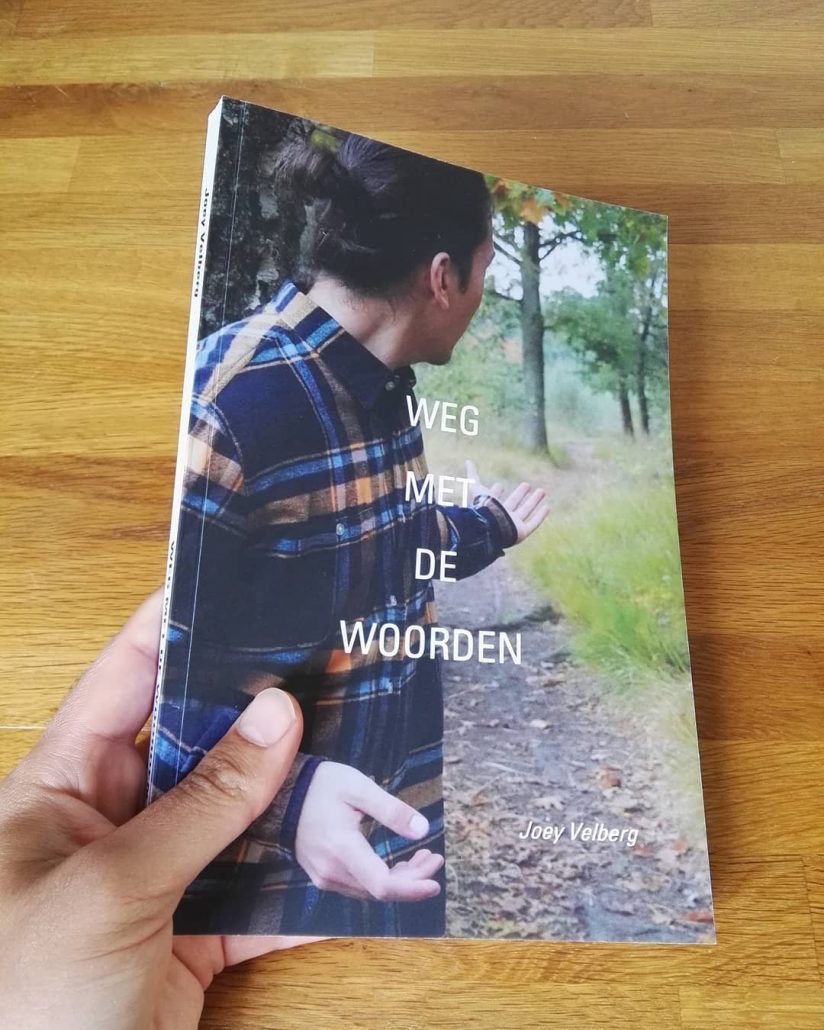

Away with words. That would most likely be the title of Joey Velbergs poetry bundle Weg met de woorden, translated into English. Note the pun – ‘away’, ‘a way’.

Joey’s way with words took him away from a feeling of alienation, on a journey of getting a bit closer to himself every day.

Together, the poems in the book shape his biography, a coming-of-age story ‘of a boy who never belonged’, ‘a queer person of color who had to find his way in a white heteronormative world’ and who – as the back cover reassures us – ‘ultimately did’.

Joey now knows his own narrative – a thing he once thought he did not have – and gladly disperses it, too. “I finally realize that I have something to add to society”, he tells me in the Amsterdam bar where we talk over tea on a Saturday afternoon. Joey took a train here from his parent’s house in the south of The Netherlands. He moved back there a few years ago.

If you’re constantly looking for a way to connect and you just cannot seem to find it… at a certain point you’re exhausted.”

Although his work is not limited to poetry (Joey is also a life coach and gives diversity training to companies) you might call it his first love.

“When I was a teenager, writing poems was my only way of escaping”, he tells me. A successful escape at that: Joey, now 30, won a national youth poetry contest in The Netherlands when he was 13. Performing his winning poem on the theater stage was the first time he remembers feeling visible. More importantly: “I felt like I was worth being seen.”

Don’t think it all changed overnight after that. It didn’t. As a matter of fact, all his experiences gradually built up to an inevitable burnout at the age of 26. Which is what made him move back to his parents; the boy who didn’t belong was finally pushed hard enough to fall.

Everything that happened before built up to that burnout?

“I feel like for an important part of my life, I have been busy surviving. That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy my childhood or adult life, but if you’re constantly looking for a way to connect and you just cannot seem to find it… at a certain point you’re exhausted.”

I always felt as if, in order to belong to this world, I had to give up a part of me.”

When it’s about burnout, you usually hear about socio-economical factors leading up to them.

“They were a part of it. I’d had a lot of different jobs at that point, from governments to startups to consultancy. Not in one of those jobs was I allowed to be me. That pushed me into burning out – the fact that companies only want to see those parts of you that are to their advantage.”

What was the tipping point?

“My already growing belief that I wasn’t fully worth existing, was confirmed when I told my boss I was burning out. She told me that she believed nothing was happening to me, that I was imagining things. ‘You have to snap out of it’, she said, ‘and just get to work.’ It was the infamous last drop.”

What happened after that?

“During the train ride home, I wrote my letter of resignation. After that my memory gets kind of fuzzy. I remember calling my mom somewhere in the following days, telling her that I had to come home. I’m so thankful my parents were there for me. I once said to my mother: if it wasn’t for your support, I might not have been here anymore.”

We order some more tea. Joey recalls a conversation with a former friend, a few weeks before his burnout. “I felt an urge to talk to somebody about how I felt. ‘The world is not for me’, I told him. ‘I don’t know why it’s like that, but it depresses me.’ He cut me short and said: ‘Joey, the world is not made for anyone. Just keep it positive, dude.’ Dumbfounded, I started making up excuses: ‘I work really hard, and I try to focus on my talents instead of the color of my skin, and, and, and.’ Until I realized: what am I doing? Why the hell am I adjusting my story to accommodate his ignorance? His way of thinking is a notoriously privileged one: ‘As long as you stay positive, you’ll have a good life.’ I don’t have the luxury to ignore reality.”

Guys either think that I’m hot because I’m Asian or that I’m not because I’m Asian.”

In the years prior to that incident, that realization wasn’t there yet – you thought it was your fault, your responsibility.

“Yes. People always thought of me a certain way. The subordinate Asian, the gay guy, the nerd, the kid who runs weird in gym class. I never had a problem with being gay myself: I came out when I was a young teen and never felt ashamed for it, but other people gave me a feeling that I should. Within the gay community, I’m marginalized as well: here, I’m the unwanted Asian. When I went to a gay club in Amsterdam a while back, my friend – who is both white and skinnier than me – was being asked to dance the entire time. The moment that someone made eye contact with me, they made sure to look away as soon as possible. Bear in mind: this is supposed to be my safe space.”

I imagine that the online realm is even harsher.

“On Grindr ‘sorry, no Asians’ was pretty much the standard reply I got. If I wasn’t rejected, I’d be objectified or fetishized. Someone once sent me: ‘I want to lick your abs and small feet.’”

Joey laughs: “I replied: ‘My abs are hidden and my feet are quite large.’ But jokes aside, it’s hurtful. Guys either think that I’m hot because I’m Asian or that I’m not because I’m Asian. They overlook the fact that I’m a human being – one with feelings and a need for intimacy. I think a lot of people who treat me and others this way, do not comprehend just how defining that can be.”

Now, according to your book, the boy who didn’t belong found his way in the world. Can you tell us how that came about?

“I always felt as if, in order to be a part of this world, I had to give up a part of me. Now, I realize there’s nothing wrong with me. I am a part of society. I choose to be authentically me – a me that is not bound by the heteronormative, white world. That way, you can’t lose.”

I realized I had a choice to let go of people’s expectations altogether.”

How did poetry contribute to that change in attitude?

“Thanks to poetry I got to realize life is mine to live. It helped me put my experiences into words, and gave my subconscious a voice. Once it’s on paper, a poem acts like a mirror. There’s one in which I wrote: ‘People treat me based on what they see, and I adjust my behavior gradually’. Writing this poem made me realize I erased certain parts of my identity in order to be more suitable to others. That was confronting, but it also showed me I had a choice to let go of people’s expectations altogether. Through writing that particular poem I was able to make a conscious choice not to accommodate. By writing my stories, I was able to truly connect to myself, acknowledge myself. Thus, they helped me become myself.”

Do you recall how it was to write the poems that changed your view on life?

“During my burnout, I couldn’t do anything for more than a year, including writing. When I regained the energy to go outside for a walk, I started writing again. In doing so, traumas from the past revealed themselves to me. That’s how I remember being sexually abused at the age of five. Slowly but surely, I started to finally comprehend how much pain there was behind my breakdown.”

Did you experience similar revelations before when writing?

“Looking back, I feel a lot of signals were already present. Some of the poems I wrote earlier in life were very dark. At the time, they did not make sense to me. But because I loved my art, I always just let it be. I feel like my words prepared me to come to the point where I was strong enough to face my demons.”

How do you feel when you read those poems that take you back to those dark thoughts?

“I have processed what happened to me, so reading them is fine. Moreover, I feel grateful for poetry to exist in my life and for it to have healed me.”

And hopefully, your poetry can heal other people too.

“That’s my goal. It’s what I believe I’m here to do. For a long time, I thought I wasn’t worth being here – now I realize that stories like mine can make a difference. I believe we need more voices like mine to open up to people’s worldviews and at the same time support those who still feel different or invisible. I feel like I am finally ready to help people with similar stories, because, well… I’m here now. Fully as myself.”

Joey’s keeping that transformation going, and, sure, you’re invited.

///////////////////////////////